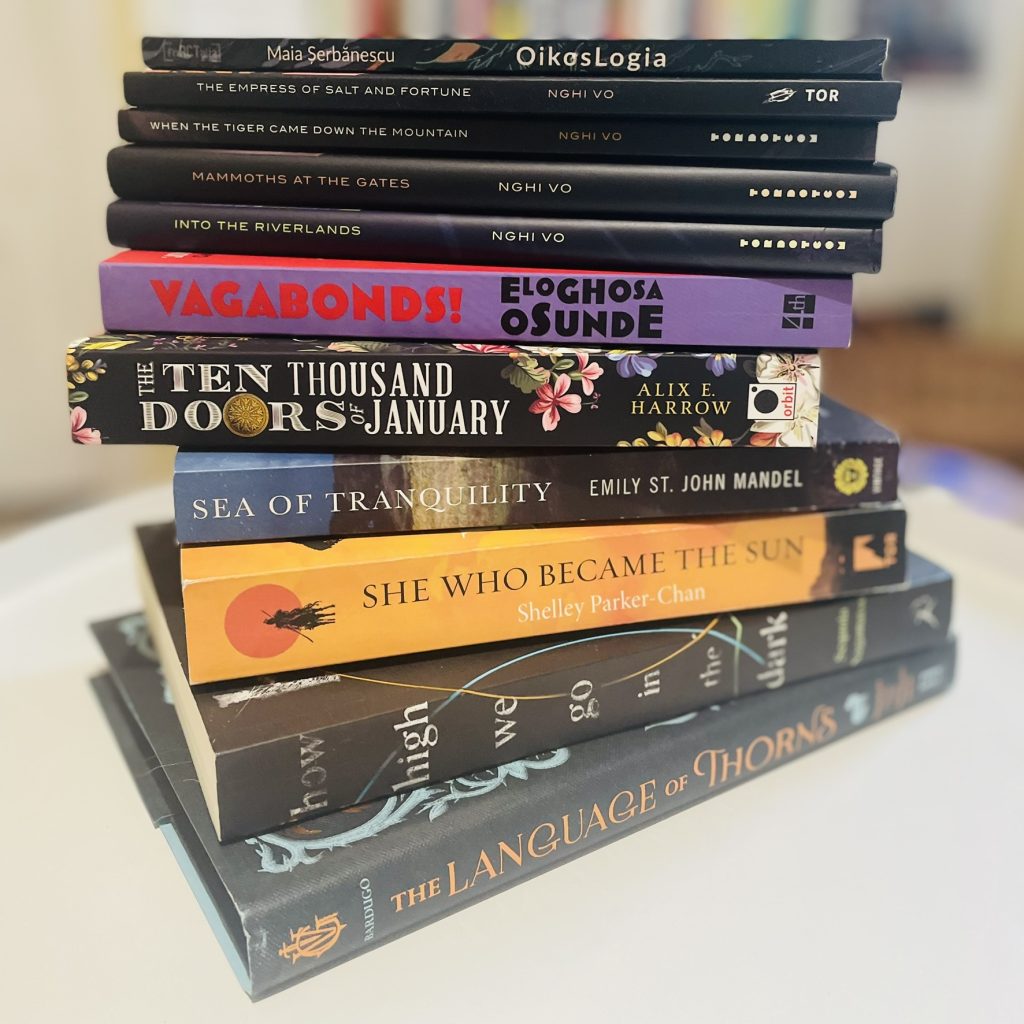

10 speculative fictions I read and loved in 2023

Because I love lists & speculative fiction & remembering what I thought about what I read, I’m making this one – it has no order except kind-of-a-chronological order? And it contains a bit of cheating because the last two I finished in 2024 and The Singing Hills Cycle is actually four novellas, but hey, I make the rules here. Below I’ll retrieve all the reviews I wrote throughout the year and at the end of each, I’ll invent a reason why a particular book would be for you. Beware, a few small spoilers ahead (especially for Chambers, Parker-Chan & Harrow). And because this is going to be the length of a bulky zine (I will not do separate entries because… time doesn’t bend to my will in this reality), I learned how to “anchor” each title so you can click on whichever you’re interested in and it will take you right there. 💗

- “How High We Go In the Dark” by Sequoia Nagamatsu

- “Sea of Tranquility” by Emily St. John Mandel

- „The Language of Thorns” by Leigh Bardugo

- “To be Taught, If Fortunate” by Becky Chambers

- “She Who Became The Sun” by Shelley Parker-Chan

- “Vagabonds!” by Eloghosa Osunde

- The Singing Hills Cycle by Nghi Vo

- “Power to Yield and Other Stories” by Bogi Takács

- “The Ten Thousand Doors” by Alix E. Harrow

- „Oikoslogia. O narațiune teoretic-speculativă” by Maia Șerbănescu

Ps. The picture is missing “To be Taught, If Fortunate” by Becky Chambers & “Power to Yield and Other Stories” by Bogi Takács (which has a beautiful cover and will come out in 2024!).

“How High We Go In the Dark” by Sequoia Nagamatsu

I don’t actually need to retrieve this one because it’s on the website already and it is quite long. But I’ll say this: “How High We Go In the Dark” made me think about a lot of things and it still stays with me months after I read it, with its careful consideration of the implications of a devastating pandemic, in the long-term. It’s written before 2020, mind you.

You’ll like this if: You’re in a pool of grief. You still want to read about pandemics. And you like understanding multiple perspectives on a world-changing event.

“Sea of Tranquility” by Emily St. John Mandel

An enveloping journey through time and space, “Sea of Tranquility” by Emily St. John Mandel connects seemingly unrelated people in a loosely knit story around the one big question: what gives meaning to a life? Spanning five hundred years, from 1912 to 2401, the cast of characters almost meet at a glitch in reality, a rupture that bleeds space/times together: there is Edwin, exiled by his rich family to another continent; Olive, a successful writer from the moon colonies who tours the Earth for her book, a pandemic novel; Mirella and Vincent, two close friends, estranged by the terrible misdeeds of Vincent’s husband; and finally, Gaspery Roberts, a detective from the Night City, whose explorations tie everything together.

Mandel’s writing style is sharp and vivid, every character inhabits the world perfectly, even a “glitched” world, one whose reality is questioned. At the center of each of their stories is, no more, no less, the answer. Not whether we live or not in a simulation of reality, not whether the timeline is set in stone, or whether there’s free will, but whether it matters. And what matters. The sweetness of their relationships, the pace and rhythm of their thoughts – especially Olive’s avalanching knowledge on epidemics, marking the book with lived & felt experience of COVID-19 -, the way you can love a time-traveling cat, and the universal longing for home – even if it is the moon – all of these will stay with me. Mandel crafts a universe which eerily reminds me of her wonderful Station Eleven (clearly, the referenced novel Olive is touring for, which in this book is called Marienbad), with its peoples meeting at points in time/space, changing each other’s lives irremediably, out of humanity, and love for the other.

You’ll like this if: You’re tired of the age-old-question of what makes life worth living. Or maybe you’d still wonder, but on the moon. Also, you can stand, or even like, reading about time-travel and pandemics.

„The Language of Thorns” by Leigh Bardugo

Take this book with you on a cold winter night. From its dark hardcover with golden embossing, to its superb illustrations and lyrically re-spun fairy-tales, it will warm you up in a coat of magic.

„The language of thorns” by Leigh Bardugo is a collection I wish I had found earlier in my life: if so, I would have known what feminist myths can be like. I loved almost all of the stories, they’re some of the best fairy-tales I’ve ever read. While they are set in Grishaverse and the lands of Ravka, Kerch and Fjerda, they can be read and enjoyed by anyone, familiar or not with this world. They stand each on their own, and even more powerfully together, as one learns to read the visual language of Sara Kipin’s illustrations, building with each page a new meaning, up until the very end.

From the first story, we know we’re in a land where the usual fairy-tale expectation is turned upside-down: the monsters are not quite monsters, those who seem at first evil might not be, and the beautiful princes aren’t all that brave. Each tale subverts a common fairy-tale expectation: the innocent girl incapable of cruelty, the mean step-mother, the magical and always-available helper, the will of the maker and the made, the value of friendship. Each account takes us into worlds in which girls can figure things out for themselves; in which men become cruel not in themselves, but because of their power; in which you’d better listen to what those close to you say and let go of your pride every now and then. It’s only „The Solider Prince” that I didn’t like as much, maybe because I wasn’t familiar with the original, or maybe because I didn’t get its point entirely and it was a tad creepy. I’ll recall „Little knife” as my favorite, for its ending, which I’ll quote here (it doesn’t spoil too much):

„Follow the voices of your worried companions and perhaps this time your feet will lead you past the rusting skeleton of a waterwheel resting in a meadow where it has no right to be. If you are lucky, you will find your friends again. They will pat you on the back and soothe you with their laughter. But as you leave that dark gap in the trees behind, remember that to use a thing is not to own it. And should you ever take a bride, listen closely to her questions. In them you may hear her true name like the thunder of a lost river, like the sighing of the sea.”

I am delighted to have encountered such a book, sour and sweet, an absolute feast.

You’ll like this if: You need a poetically-spun feminist fairy-tale to get you to sleep at night.

“To be Taught, If Fortunate” by Becky Chambers

A sweet, nerdy, easy-to-read yet philosophical story about humanity’s place in the universe, “To be taught, if fortunate” by Becky Chambers takes you on a scientist’s journey to four planets, surveying possibilities for life beyond Earth. We’re taken on this slow, sinuous voyage with four queer characters, entangled in close, beyond-kin relationships, on a small spaceship equipped with somaforming technology – changing their bodies to adapt to the environments they explore.

It’s the first book I’ve encountered in which interstellar travel in torpor (a form of dreamless sleep) happens in time, and characters actually age, having to go through a ‘hygiene’ ritual before starting to work when they wake up – cutting their nails, hair, and more. This attention for the little, mundane things is, I believe, a mark of Chambers’ writing, and in this short book it sets the stage for the kind of story that is to come: a narrative about mornings, work-lives and love-lifes, a space opera of small things, where we are given nerdy lists of objects astronauts need and protocols they follow. I enjoyed the simplicity with which the science is explained and the way it enters the story, part-and-parcel of it, never too much.

The book problematizes space travel as an enterprise in itself, raising the questions of whether we should, under what circumstances, who should pay for it, and if yes, how to do it. Planet Earth is far, and yet its destruction is close, as the astronauts get messages of news with impending climate disasters, wars and violence – a future we, right now, are quite aware of. Searching for other worlds, the explorers try to intervene as little as possible, changing their bodies to suit them (glittering in the dark, withstanding a greater force of gravity, or more radiation) and using special cameras to study life-forms, rather than dissect them.

“I’m an observer, not a conqueror. I have no interest in changing other worlds to suit me. I choose the lighter touch: changing myself to suit them.” /14

It is important to note that, ultimately, what I believe caused tension between the four of them was their existentially at-the-margin situation, the meaning and implication of their work (rather than their queer, poly interpersonal relationships – in Chambers’ style, queerness is embodied in the sci-fi world with ease). Having unwittingly caught an alien creature within their ship and having to kill “it” for contamination reasons makes a wound between them, one that has no time to heal as they enter torpor and travel to the next planet soon after. Chikondi, one of the characters, is the most affected by the experience, essentially questioning their anthropocentric endeavor “Is it fair to the worms, to cause them pain so that I can know more about them? (…) Is that a fair trade, their pain for our knowledge?” (p.96). Ariadne, the narrator, is a comforter – she keeps easing everyone’s feelings about the fact: Chikondi’s, who had to do the killing; Elena’s, angry because of the protocol break; and Jack’s, distressed because of the entire situation. Their context becomes even more dire as news from Earth ceases to arrive. The open ending drags us deep into the questions they have been exploring – it might seem absurd to some, but to me, it seemed to be the unlikely outcome of all that has been happening. Unforeseen, and yet it made sense.

“Everything we do, we do on the shoulders of others.” /134

You’ll like this if: You want to see queer scientists doing smart things in space. But also, you wonder if we should be colonizing space at all?

“She Who Became The Sun” by Shelley Parker-Chan

“She Who Became The Sun” by Shelley Parker-Chan is an epic of war, conquest, fate and desire, with two queer protagonists at its center. The book is as grand in its larger-than-life battles and political scheming, as it is fascinating in its understanding of gender as a driving force of its action. I will run along some of my thoughts on it below, mainly on how I found that the two character’s relationships ‘made’ the book great, and how their queerness is constituted – some spoilers will come up.

From the very beginning, we enter a world of famine and violence, in The Great Yuan, cc. around the 1350s. We meet a girl, whose name we soon forget – if it is ever mentioned at all. Her family is poverty stricken, her siblings and mother are dead, and food is nowhere to be found. From the first moment, we are given the knowledge of how patriarchal gender norms shape the world: “The girl knew that fathers and sons made the pattern of the family, as the family made the pattern of the universe, and for all her wishful thinking she had never really expected to be allowed to taste the melon” (p. 16). This state of things doesn’t last long, as soon her misfortune grows so big that only her sheer will helps her survive, and an idea: she will impersonate her brother, Zhu Chongba, who was supposedly destined for greatness. Dressed up as him, taking his name, she sets forth on her path to make history.

Her first ‘home’ is a monastery, an abusive institution who instills discipline in its monks – it is also the place where she makes her first true friend, Xu Da. It is there that we meet the second ‘central’ character, so to say: General Ouyang, an eunuch, whose main drive is revenge for the killing of his family, for his enslavement and his castration. Slowly, it grows on the reader the fact that the two characters who end up being at war, Ouyang and Zhu, are somewhat “alike” in being gender outlaws, inhabiting bodies that do not conform to social expectations. Ouyang’s relationship with his master, Esen, is one of the most excruciatingly painful to observe, the general having to withhold an ocean of complex, heavy feelings towards Esen: both love and anger, attraction and hate. Ouyang’s central emotion is shame (“The body became used to exercise, particular sounds and sensations, or even physical pain. But it was strange how shame was something you never became inured to: each time hurt just as much as the first.” p. 131), Zhu’s driving core is pure ambition towards “greatness”, a desire that disrupts everything else, that teaches her to kill, to ambush and to betray, to do whatever it takes to refuse her first fate – “nothingness”. For Ouyang, “The worst punishment is being left alive.” (p. 326), but for Zhu, who “had never borne any ancestral expectations of pride or honor.” being alive, even if disabled, only means she still has a chance to succeed.

For me, what made this book irresistible to read was precisely the exploration of how the two inhabit gender and navigate their relationships from each specific embodiment. It was fun to see how Zhu rose from a poor peasant to a monk and then a leading general – a coming of age in power – using her wits and (surprise surprise) her understanding of women as humans. Never underestimating them, not once, she sees things that a man would not have noticed. Her relationships with Ma, the woman she falls for, and Xu Da, her best friend, hold and steady her when she cannot. The sweet, queer relationship with Ma Xiuying (who is shown desire by Zhu, who would have not otherwise “wanted to want” something else of her life but being in her place) grows heavier, darker, as Zhu’s actions become more violent and remorseless. Even her enmity with Ouyang is multifaceted, as Zhu always sees in him a sort of alikeness – one that Ouyang doesn’t know about, and would have hated, bearing a deep seated misogyny inside himself.

Ouyang and Zhu’s feelings of gender dysphoria are not the same. While for Ouyang, being denied his masculinity or being told he resembles a woman bears the worst of shame, Zhu is neither man nor woman – in her drive to survive, inhabiting her brother’s life has provoked anxiety in her only at the idea of being discovered, of not succeeding. It’s not the embodiment of a different gender that bothers her, ultimately, but the difficulty to place herself in a binary world, to recognize and find pleasure in her own body as it is – which we learn much later, from her relationship with Ma (“Zhu didn’t have a male body – but she wasn’t convinced Ma was right. How could her body be a woman’s body, if it didn’t house a woman? (…) I’m me, she thought wonderingly. But who am I?” p. 341). Ouyang’s relationship with Esen is like a mirror to Zhu’s relationship with Ma, unfurling simultaneously in their brutal sexual tension, but going in very, very different directions. Both their determination to do ‘what needs to be done’ brings the story forth to its culmination.

When I started reading it I kept seeing Mulan in this story, but as I went forth I realized the similarities are only a handful: yes, a girl dresses up as a man and becomes a soldier. But everything else is of a different fabric, and the ‘happy’ ending we are given is not truly joyful, but rather ominous, like storm clouds gathering on snow-laden mountaintops. Looking very much forward to the next in the series – He Who Drowned The World.

You’ll like this if: You want to see complex, gender-bending characters achieving power without mercy. And you just want to get lost in a larger-than-life, scheming, violent political intrigue, far away from the present…

“Vagabonds!” by Eloghosa Osunde

“Vagabonds!” by Eloghosa Osunde is a swirling hurricane of energy, of queer debauchery, of pain, money & poverty wrapped tightly in a stylistically unique bound. It’s more of a collection of stories spewed by a flaming volcano burning right in your hands than a novel, really, but the connection is there: the city of Lagos. Its gods. Its inhabitants. Its powerful and its powerless.

Vagabonds! is a sort of ode sung for the queer Nigerians, for the desire of pleasure, of freedom to touch flesh and adorn oneself in jewels and luxury. Moreover, it bends fantasy and reality as it ends by considering the 2014 anti-queer Nigerian law, including how it affected some of the characters in the book.

A few words on my favorite short-stories/chapters:

Overheard: Fairygodgirls – disappeared, young or dead, these fairygodgirls know exactly which book an alive girl needs to read to save herself, her sanity or her soul. Each fairygodgirl makes it so the book appears next to the needy reader, recommending, for example: Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid, Pet by Awkaeke Emezi and The Icarus Girl by Helen Oyeyemi. “Together, they make the holiest God you’ve seen – the kind young girls have deserved all along.” /84

Rain – about Wura Blackson, a fantastic dress-maker, and her desire for a daughter, who becomes Rain: “This was one of the endless wonders of her: she could switch between ages, between genders, between temperaments, whenever she so pleased.” /115

After God, Fear Women – where women suddenly disappear, “This God was a genderbender, a multiplespirit, an Above and Beyond”. /143

There is love at home – about a lesbian couple & their BDSM job. “We’re ghosts because we have to be, because our lives depend on passing and being passed by.” /209

I’ve had my eyes on it for a long while and I’m glad I finally got to read it – and pretty happy to have it marked on my Read the World Challenge as my Nigerian read (though of course it won’t be my last Nigerian read – who would do that to themselves?!). Osunde’s book is sensual and overspilling with both pleasure and rage. It’s a book about queer survival written with such a specific, smooth sound, having worlds stitched together like a shiver in a sand-dune, and then a sudden earth-quake.

You’ll like this if: You like to be dazzled by queer (short) stories in all the ways & you adore sinuous, sensually written prose.

The Singing Hills Cycle by Nghi Vo

The Singing Hills Cycle swings you into its world of magical tales and lulls your soft body into a story, as if you were a child. It is a wonder to fall into for a few afternoons, and I am glad I ended the last days of 2023 reading the four books that appeared until now.

The Empress of Salt and Fortune is a tale of a friendship across class/status, of myths being born and of two spirited, smart young girls making do with their lives within the empire.

Cleric Chih (nonbinary human) and neixin Almost Brilliant (a magical bird with great memory) travel across the countries to collect stories and so, they meet Rabbit, servant girl of In-yo, The Empress of Salt and Fortune. In her old age, Rabbit slowly recounts the tale of ascension to power of her friend and master, their lives before the coronation, the hardships, the joys, the laughs and the games. It is a story about heartbreak and love and magic at court, made spicier by a much too short sapphic affair.

When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain is a story about the two sides to every tale – to be read in one sitting, ideally in the nights of winter with a hot cup of tea by your side as the fire is crackling. It follows non-binary cleric Chih from the Singing Hills as they travel with northerner Si-yu and Piluk the mammoth and become stuck facing three tigers, at their mercy. To appease them, Chih starts telling them the story of great tiger Ho Thi Thao and her lover, as they have known it from the accounts of other humans. The tiger sisters are curious, but displeased – this story doesn’t match what they know, what they as tigers tell each other. They intervene in the tale and often contradict the cleric, asking them to write their own version down. Thus, at key points, we are given two perspectives – the human’s and the tiger’s, the story splitting in two or sometimes even more versions. It reads like a beautiful fairytale about how the teller of the story makes the story their own, about queer love (in more ways than one) and the wit needed to survive.

It’s interesting to me to notice how I connected to this story more than to the first one, and why. Neither stories delve deep enough into Chih to care about them, so it must be the way the story changed once it was told by the tigers, the little details of the tiger world – their sayings, their customs, what marriage meant to them and how different from, and yet similar to, human marriage it was. This clash between two cultures – shapeshifting tiger and human – was what wrapped this story into a magical bundle for a prolonged afternoon.

Into the Riverlands – Cleric Chih and Almost Brilliant (a neixin / magical bird) are out to another adventure in the third installment of the Singing Hills Cycle.This time, they become part of the story as their travel companions (two sisters and a middle-aged couple) unfurl the tales of the region about legendary fighters and bandits – all the while being constantly attacked.

Multi-layered, holding stories both within the narrative framework and with each character who chooses to tell one (while some choose not to), this third book I didn’t like as much as the others, though I like how the themes connect and the entire universe has grown on me. While the first book contained games as a “key”, the second a poem, the third one has a theater play in its midst, among its many other small tales and action-packed sequences of “Southern Monkey” martial arts. This novella also sketches out the magical universe further, as we are met with spirit boars as well, beyond tigers and foxes. The spin at the ending was nice, but it took me a while to be convinced I got it right, because there were way too many names to remember (for me). Though it is nice to be shown how people are given different names based on who knows them, and how. I also love how all of Vo’s stories center feminist or queer characters, resistant to patriarchy at least in some ways.

“The world is built on who carries what and for who,” Chih said, settling the weight more comfortably on their shoulders. “It’s not a bad world where we carry presents for people who feed us.” /65

Mammoths at the Gates is a magical story about grief and the many faces of each person. The fourth in the Singing Hills Cycle by Ngho Vo, this novella follows Cleric Chih as they arrive back home at the abbey, only to find their teacher, Cleric Thien, dead, and their childhood friend Ru now left as overseer. We finally learn more about Chich and about the neixin, fantastic bird-creatures with unfailing memory, who dwell within the abbey and work alongside the cleric to record history and story alike.

I loved the pacing of this one, but I was a little disappointed in finding the ways in which this fantastical world, too, is anthropocentric, with man/human being the most important being almost unquestionably, despite not being the only one who “speaks”. Another pitfall of speciesism is that only beings who speak human language are regarded as valuable – which is why neixin are considered persons, not beasts. Even so, their entire existence is centered on recording human history, not neixin history (as if they don’t even have a history of their own). Myriad Virtues, who was Cleric Thien’s neixin throughout his life, is so overwhelmed with grief so as to transform themselves, never to be the same again – but when asked to be put at the people’s table, she is initially denied. Ultimately, the extraordinary nature of the neixin is compared to the ordinary non-human animals who are considered incapable of such great grief. The exceptionality of some is, once again, constructed in a hierarchical binary against the (presupposed) incapacity of those who are nonhuman/nonpersons.

Despite these flaws, I felt deeply engrossed in the tale. It is touching and beautiful, and makes me look forward to the next installments.

“This was someone new, and something in Chich ached, because growing up, growing older, was always a kind of loss, even if what was gained repair it all and then some.”/ /78

You’ll like this if: You like sitting down & falling for hours into a world of shapeshifting creatures, queer empresses, magical birds and fairy tales about culture and grief and power with a feminist bent.

“Power to Yield and Other Stories” by Bogi Takács

Since the moment I opened “Power to Yield and Other Stories” by Bogi Takács, I would wait, each day, for evening to come so I could read another one of the stories. This didn’t happen to me in a while with short story collections, so what was the reason I was so pulled towards it? Probably the unique combination of speculative fiction from a particularly queer, neurodivergent, Jewish point-of-view, which added multiple layers to each and every story. We’ve got an AI with a soul who reads the Torah; a mother-turned-plant as her non-binary child is dealing with their bar mitzvah; a queer mage couple separated by a war; riots started from mysterious reasons; living vampire-like houses and their tenants; an intergalactic interspecies Pride parade in Győr (in Hungary!) and a planet that asks too much of some of its residents – just to name a few!

“Plantiness” is one of the first states I observed as particular to this collection, the recurrent theme of plant-being finding itself in at least three stories. One of them is “Folded into Tendril and Leaf”, which I loved. It tells the story of queer love between two mages, of whom one becomes a water caltrop for much too long: “I gradually eased into the days and into my new existence. The pain not so acute, the pain in the soul. The lesson being learned deep in the body.” I can’t help but think of Natasha Myer’s work on the Planthroposcene and her concept of “becoming sensor”, “vegetalizing” and plant-feeling, which I encountered working on this video-essay on plants. Plant-time and plant-feeling are touched upon, again, in the stories “And I Entreated” (which delves into family dynamics with a Jewish non-binary child) and the very short, poetic and fantastical “The Third Extension”.

Another main theme is difference and identity of multiple kinds – in culture, sex, gender, class, language, body/mind. Neurodivergence as we know it is a close cousin to what is fittingly termed “cognotype distribution” in a universe of multiple species. This attention to the different ways the mind might work pops up a lot, as does the experience of being Jewish and/or queer and being perceived as such by others (who might look upon with recognition or judgment, as is the case in “On Good Friday the Raven Washes Its Young”).

In “Volatile Patterns” we have a clash of cultures – a couple who are called māwalēni in their own language and “wizards” otherwise, investigate the causes of a mysterious riot. It turns out to be both a disturbing and fascinating case of cultural appropriation. The difficulties of intercultural communication are further explored in “The 1st Interspecies Solidarity Fair and Parade”, where after multiple alien(s) invasions, a call for peace and discussion is made, brought forth by a disabled character and an extraterrestrial sphere – in the fields of future Hungary! I loved reading such a story set in Eastern Europe, and only wish that “interspecies solidarity” would include non-human animals as well.

One of the most interesting stories, to me, was “A Technical Term, Like Privilege”, which intersects class, species, status and gender in such an interesting manner that it would prove a striking discussion start for a study group. Within this story-world, house-beasts feed on the blood of their tenants – until one of them rebels, not wishing to give up all of his life-energy just to have a roof above his head. What a metaphor, right? Staring into your face is a scream against the housing crisis, but a beastly sort of scream, with the house and the tenant in unison against the profit-makers.

The collection ends with short content notices as some difficult themes are touched upon and bonus notes about the author’s inspiration for each story – which I always like reading, ever since I first found them in one of Ted Chiang’s books. I was very excited to be able to read “Power to Yield and Other Stories” before its publication as I was sent a digital copy from the author for an honest review, which is a small price to pay for such a queer wonder of a book!

You’ll like this if: You love short speculative fiction written with attention to difference, identity and power, and are totally into reading what’s written from a queer neurodivergent Jewish perspective. Also if you wonder what it would be like to be a plant. And you hate paying rent.

“The Ten Thousand Doors” by Alix E. Harrow

“The Ten Thousand Doors of January” by Alix E. Harrow is a charming love-letter to stories and to the force of the Written; a sweet, much-too romantic tale of love; a magical coming of age and beyond it all, a critique to colonialism, racism and the civilizational discourse of progress. I fell into this book as the new year opened and barely emerged a few days later, entrapped by Harrow’s flowing writing style and her universe of doors to anywhere – which I love, love, love, and am mildly disappointed it was not explored to its full length, maybe even in a sequel.

“If you are wondering why other worlds seem so brimful of magic compared to your own dreary Earth, consider how magical this world seems from another perspective. To a world of sea people, your ability to breathe air is stunning; to a world of spear-throwers, your machines are demons harnessed to work tirelessly in your service; to a world of glaciers and clouds, summer itself is a miracle.” /141

The book follows January Scaller, a young “in-between” girl protected by a wealthy Mr. Locke, with no mother and an always absent father. Throughout the novel, she discovers the truth about her father’s journeys, her parents’ love story and her true origin, aided by her dog Bad, her childhood friend Samuel and mysterious, resourceful Jane. While in the beginning she tries to be a “good girl” and almost copies Mr. Locke’s beliefs on the nature of progress as her own, throughout the book she learns what it (truly) means to be marginalized, poor, and most of all, colored, in a patriarchal, white supremacist society.

“I should have known: destiny is a pretty story we tell ourselves. Lurking beneath it there are only people, and the terrible choices we make.” /246

This book is smack in the middle of being a magical fantasy coming-of-age, an instant (unbelievable yet incredibly sweet, cis hetero) love story and a rebuttal to powerful white men ordering and bending the world to their will. The Doors to the endless many words bring change, we are told, and this change, while it might not always be good, at least it’s always troublesome for those who wish to form the world after their image and desire entirely, pushing others to the brink.

“I wonder sometimes how much evil is permitted to run unchecked simply because it would be rude to interrupt it.” /346

Ultimately, it is, profoundly, a book about and against racism, understood not only as a prejudice/discrimination, but as a colonial way of ordering the world. Coming from a white author, I was/am a bit unsure what to make of it (most of the main characters are of color), yet I am reminded racism IS a white-people problem, and writing with that in mind is what we should all consider doing. Moreover, the story deals with the interlocking of race/gender/class/madness as we are shown that January can be easily incarcerated in an asylum if her wealthy guardian deems appropriate. Its setting in the early 1900s USA is appropriate to mark a time in which there was little freedom for girls of color and in which revolutions seemed to be in the past, a time in which racial segregation sweeps deeply into daily life and in which proximity to whiteness is privilege, but not entirely (in the case of Samuel, who is Italian). I also liked the book-within-the-book scheme with its scholarly annotations because I am a nerd, of course (like this: “Yule wondered if all scholars dedicated their lives to questions that other people had already casually answered, and if they found it vexing or pleasing.” /179)

So if we are to look at some of its flaws, yes, the protagonist often makes silly mistakes so the plot moves, she is often “much too special” like in any YA trope, everyone kind of loves her, the dog is a perennial ward with no real desires of his own (and gets hurt a lot), and the pacing is unequal at times (slow in the beginning, too fast in the end). But I kind of really loved the book, with its magical deep-dive into a world-not-unlike-our-own, its belief in the power of the written word to stand up to patriarchal power and its beautiful prose-writing style. And Doors to other worlds! What else can you wish for, really?

You’ll like this if: You love portals, coming-of-age stories & criticizing colonialism. You’re into writing that is beautiful, flowy, bookish. And to really enjoy it, you should have a high tolerance for teen protagonists who do silly things & instant (cishetero) romance.

“Oikoslogia – o narațiune teoretic-speculativă” by Maia Șerbănescu

A strange hybrid of theory and speculative fiction, “Oikoslogia” by Maia Șerbănescu imagines a socialist, feminist, queer text-world in which there is no longer an ”outside”. The book begins with an introduction by Iulia Militaru, who explains that Maia Șerbănescu is a project where she tries to “demonstrate the capacity of alternative worlds to develop critical thinking”. The introduction thoroughly places the text in a political space dedicated to community and regeneration, beyond capitalism, speciesism or racism. And then – one finds themselves in a swirl of voices and images, an alien world of the habitants, transformed humans and non-humans living together in a connected colony in which time/space bends without direction. Plastic and hunger remain of the past world, but the only “thing” to be eaten are earthworms – no other being is consumed. The narrative follows one habitant, Maia, but then switches perspective: one finds themselves away from the text in a theoretical exploration, then back in, sometimes in first person, sometimes in third person, sometimes following another character altogether. Or is it another character? The passage from one type of text to the other, from one voice to the other, marks the queer, uncategorizable aspect of this book, which breaches literary genres with intent, knowing the damage it does.

Talking alongside writers and cited theorists such as Karen Barad, Ocean Vuong, Jeanette Winterson, Laura Sandu, Sofia Smidovici, Lizzie O’Shea, Alison Kafer and José Esteban Muñoz, “Oikoslogia” becomes a feminist breach into the literary world, sustaining that literature most not be a tool for domination, but for inspiration – it should nurture the resistance of the oppressed rather than quiet it. You can only read it in Romanian, for now.

You’ll like this if: You like your mind-thoughts to bend & fracture into an ungovernable alien world in which socialist-queer-feminist theory seeps in like a fog, marking everything with its mysterious touch.