Dark & Cold Water Worlds – The Deep & Blackfish City

I’m still softened by just having finished “The Deep” by Rivers Solomon, listening to Drexciya and trying to gather my thoughts, waving like seagrass. Just a few days ago I also finished “Blackfish City” by Sam J. Miller, which is why I’m writing about both of them now, still fresh in my mind. They both embody worlds of water, one colder than the other. They’re both concerned with climate change and filled with queer characters, and they’re both speculative fictions, but the similarities kind of end there. Blackfish City is gritty and noir and action-packed, you can smell its dangerous street corners and follow its fast, fighting characters. The Deep is dark in multiple ways, both nurturing and terribly painful, it is a world of sound and vibration whose pace is that of myth. Below I’ve tried to write a bit about them, in my quest to write some words about every book I read, and just a tad more about the ones I really enjoy.

Blackfish City by Sam J. Miller

How will life be after societal breakdown, after the climate wars? In “Blackfish City” by Sam J. Miller we read about the extreme poverty and extreme richness, the gang leaders and shareholders plotting their way upwards, the fighters trying to survive, gay sex and a fascinating woman from a peoples killed, sailing with an orca towards a floating city in the Arctic Circle. There’s a mysterious disease affecting many people – the Breaks – and unknown software running the city, inequality and a dire housing crisis.

“Fine line between good business and a fucking war crime,” he said.

“Ain’t that the goddamn epitaph of capitalism.” (p. 306)

“Blackfish City” is certainly one of the contemporary science-fiction books to read on the housing issue. Housing becomes the core and center of the novel’s plot, besides many other strands being picked up – of science gone rogue, ethnic cleansing, immigrant worker exploitation, and a strange “nanobonding” between human and non-human animals. It’s a world exploding with today’s issues, all crowded in the city of Qaanaaq, tall and rowdy, full of crime, protest and delicious noodle stalls. It’s not surprising to read in the author’s description that he’s a community organizer because honestly, the novel is built on the attention to detail he gives to the social issue of housing.

Jumping from one point of view to another, we’ve got Fill – a young gay man who’s economically privileged and kind of sex-obsessed; Kaev – a beam fighter who has trouble communicating; Ankit – an ex-scaler (parkour climber sort of), council-worker and Kaev’s sister, Masaaraq – the orca woman, following an unknown, dangerous purpose, ready to kill for it, and Soq – a nonbinary youth who had to fend for themselves, trying to climb upwards by getting in Go’s, a gang leader, favors (“Soq was beyond gender. They put it on like most people put on clothes. Some days butch and some days queen, but always Soq, always the same and always uncircumscribable underneath it all.” p. 42). Interestingly, the chapters are often separated by a “City Without a Map” broadcast, a sort of podcast for whoever listens – the rags and the riches, as it is enjoyed and hated by people of all kinds – whose Author is unknown and whose importance to the plot grows as one reads on.

“Villains can be stopped. But villains are oversimplifications.” (p. 309)

With jaw implants that translate all languages, buildings that change shape for security reasons, and humans who (kinda) control the animals they are nano-bonded to, with desire to conquer and lust for revenge, this novel is packed full and feels a bit too much, just as Qaanaaq probably feels like. I won’t spoil it, but safe to say the action keeps raising and gathering speed towards the end as more keeps happening – revelations on the arrival of the orca woman, the connection between the characters, the cause and cure of the Breaks (which initially seems similar to the AIDS epidemic) and most importantly, the way to save one’s family while fighting landlords (though kind of requiring an orca ally… well, one is reminded of the killer whale’s attack on yachts, isn’t it?).

My main criticism is that I wish more thought had been given to the human-nonhuman relationships, as the nanobonding peoples are quite central to the story. The non-human animals (the orca whose name we learn far too late, the polar bear Liam, the monkey Chim) don’t get to have much depth and although they do influence their human bonders, it seems like the whole point of the relationship is for it to work in favor of the human, foremost. Besides, bonding to an unknown animal for life kind-of-seems like (forced) marriage to a stranger, but 100% times worse, because you always feel what they feel, never a moment’s respite (from both sides). Unfortunately, it’s a missed opportunity to truly explore what bonding beyond species might mean.

All in all, it’s a wild ride, a bit rocky at the start and speedy at the end, but certainly interesting. Blackfish City’s world feels raw and cold and very true, a mash-up of different real and imagined cities, a gritty place to return to imaginatively and be wary of when organizing for a different future.

“Stories are where we find ourselves, where we find the others who are like us. Gather enough stories and soon you’re not alone, you’re an army.” (p. 224)

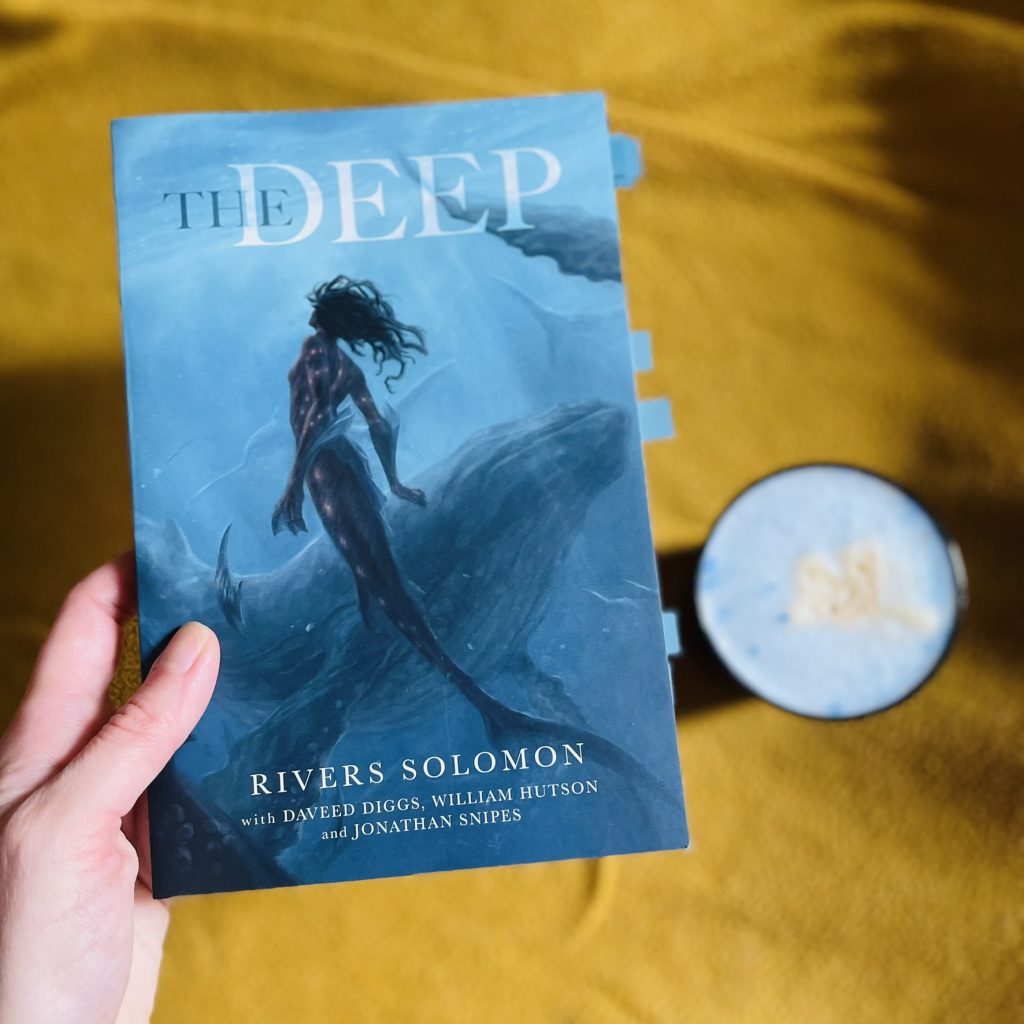

The Deep by Rivers Solomon

A novella that takes you deep into a fully-fleshed world of darkness and sound, a meditation on the essence of remembering, history and identity, “The Deep” by Rivers Solomon is a read you want to jump into all at once. Its currents will take you through warmth & coldness, as the pain of the African people who have died in the trans-atlantic slave trade, thrown off ships, becomes core and center in this antiracist, anticolonial imagining of survival.

It all starts with Yetu, the historian, tasked with remembering all her people’s experiences, since the very moment they started breathing underwater. A cluster and a multitude of too much sound, vibration and image, the History is a lot for Yetu to take in, and yet she must. The superb descriptions of living on the ocean floor and of Yetu’s perceiving of the world around her detail sensory over-stimulation – Yetu was chosen to be a Historian because she was particularly perceptive, which could be translated (in Western terms) as neurodivergent. Each year, the Remembering takes place, the celebration in which she transfers the memories to the rest of the Wajinru, as they live completely in the moment otherwise, the past being too hard to bear. But this time, Yetu won’t follow the rules. She’ll break them. And thus, this story is born, and we are swept into it, chapter to chapter, exploring the world of the merfolk Wajinru, their beginnings and their ancestors, the power of knowing where you come from, the longing for a homeland.

“Forgetting was not the same as healing.” (p. 28) is what this story tells us, a story born out of a “game of Telephone”, as explained by the band clipping. in the afterword. Yetu’s universe is built on the song “The Deep” which in turn is inspired by Drexciya, the techno-electro duo who created the initial mythology, asking: “Could it be possible for humans to breathe underwater? A foetus in its mother’s womb is certainly alive in an aquatic environment.” (p.158). A fascinating recognition of how ideas come to be and how far they can travel, this book adds another dimension to the lore by exploring the meaning of remembering – as communities and as individuals – by riffing off “The Deep”’s lyrical repetition of “y’all remember”.

I am astounded at the multimedia universe these works create together, a womb-dark, nurturing, fantastical exploration of what it can mean to resist white supremacy and climate change. They embody what it means to look at a terrible moment in history with an Afrofuturistic sort of vision. I love that it’s so short, giving it a foundational fairy-tale texture which lets you fill in the missing parts. It really feels like a story for a people. And I adore that recognition is given to the others who have contributed to the story.

“We cannot understand a people that would willingly choose to cut itself off from its history, no matter what pain it entails. Pain is energy. It lights us. This is the most basic premise of our life. Hunger makes us eat. Tiredness causes us to sleep. Pain makes us avenge.” (p. 130)

This novella moves one to look again at the past with the strange eyes, “strange fish” eyes, to never forget the trauma of History. It reminds one to keep close the force of the seas, of the waters which birthed all life. And it’s a (queer) world to return to, the mythical energies it summons being as deep as the ocean.

“What is belonging?” we ask.

She says, “Where loneliness ends.” (p. 49)